Rockville "Rox" - Parke Heritage Wolves Rockville, Indiana

Classes of 1865 - 2025

History of Indiana

HISTORY OF THE INDIANA TERRITORY & HOW IT GOT IT'S NAME

.png)

The first people to live in what is now Indiana were the Paleo-Indians, ingressing about 8000 BC after the melting of the glaciers at the conclusion of the Ice Age. Divided into small groups, the Paleo-Indians were nomads who hunted large game such as Mastodons. They created stone tools made out of chert by chipping, knapping and flaking.[8] The subsequent phase of Indiana's Native American antiquity is called the Archaic period, which occurred between 5000 and 4000 BC. They differed from the Paleo-Indians in that they used new tools and techniques to prepare food. Such new tools included different types of spear points and knives, with various forms of notches. They also used ground stone tools such as stone axes, woodworking tools and grinding stones. During the latter part of the period, mounds and middens were created, indicating that their settlements were becoming more permanent. The Archaic period ended at about 1500 BC, although some Archaic people lived until 700 BC.[8] Afterwards, the Woodland period took place in Indiana, where various new cultural attributes appeared. During this period, ceramics and pottery were created as well as the increase of usage in horticulture. An early Woodland period group named the Adena people had elegant burial rituals, featuring log tombs beneath earth mounds. In the middle portion of the Woodland period, the Hopewell people began exploration of long-range trade of goods. Nearing the end of the stage, an exhaustive cultivation and adaptation of agriculture to grow crops such as corn and squash. The Woodland period ended around 1000 AD.[8] The incoming period afterwards was known as the Mississippian period, which lasted from 1000 to 1650 AD. During this stage, large settlements were created that had similarities to towns, such as the Angel Mounds. They had large public areas such as plazas and platform mounds, where instrumental individuals of the settlement lived or conducted rituals.[8]

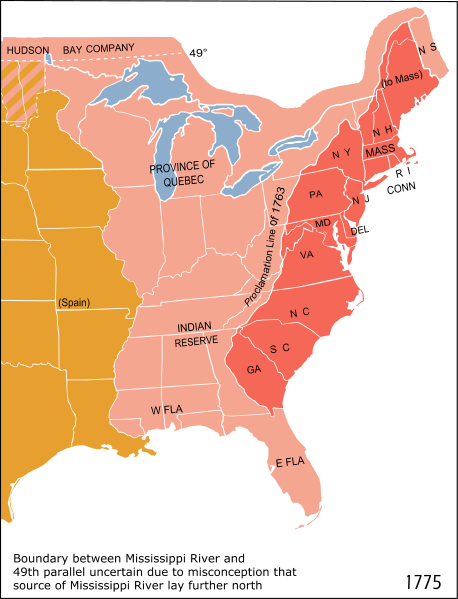

French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was the first European to cross into Indiana after reaching present-day South Bend at the Saint Joseph River[disambiguation needed] in 1679. He returned the following year to gain knowledge of northern Indiana. French fur traders also came along and brought blankets, jewelry, tools, whiskey and weapons to trade for skins with the Native Americans. By 1732, the French had made three trading posts along the Wabash River with the efforts to control Native American trade routes from Lake Erie to the Mississippi River. The oldest continuously occupied town in Indiana is Vincennes (Fort Sackville). In a period of a few years, the British arrived and contended against the French for management of the fruitful fur trade. Fighting between the French and British occurred throughout the 1750s as a result. Due to mistreatment from the British, the Native American tribes sided with the French during the French and Indian War. By the conclusion of the war in 1763, the French had lost all land west of the colonies, and control had been ceded to the British crown. Neighboring tribes in Indiana, however, did not give up and destroyed Fort Ouiatenon and Fort Miami during Pontiac's Rebellion. The royal proclamation of 1763 ceded the land west of the Appalachians for Indian use, and was thus labelled Indian territory. In 1775, the American Revolutionary War began as the colonists looked to free themselves from British rule. The majority of the fighting took place in the east, but military officer George Rogers Clark called for an army to help fight the British in the west.[9] Clark's army won significant battles to overtake Vincennes and Fort Sackville on February 25, 1779.[10] During the war, Clark managed to cut off British troops who were attacking the colonist from the west. His success is often credited for changing the course of the American Revolutionary War.[11]

At the end of the revolutionary war, through the treaty of Paris, the British crown ceded the land south of the great lakes to the newly formed United States. They did so without the input of the Indian tribes living in the area. The tribes were not party to the treaty. Some scholars argue that because of this lack of representation, Indian rights to the land were unfairly ceded to the US by the British Crown.

The Naming of Indiana

The following article appeared in the Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana Historical Society

Vol. 1, No. 1 (1903), pages 3-11, located in the Indiana State Library.

The Naming of Indiana

by Cyrus W. Hodgin

Previous to the opening of the nineteenth century, the present State of Indiana had no history except what it had in common with the surrounding territory. Her geological development, and the other phases of her natural history, did not materially differ from those of Ohio, Michigan and Illinois. Substantially the same conditions produced the soil and the native vegetable and animal life of them all.

When she was occupied by the Mound Builders and the Indians, there were, so far as we can tell, no boundaries to separate her from the adjacent lands. Under the rule of the French, she was sometimes considered a part of the New France (Canada), sometimes of Louisiana. On falling into the hands of the English, after the French and Indian War, there were no marks to distinguish her from the rest of the English claims in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, of which George Rogers Clark, as a result of which she fell under control of Virginia, she was, for a time, only part of a county of that proud Commonwealth. This county was called Illinois county. After her transfer by Virginia to the United States, she was included in the area called the Northwest Territory, and still had no separate name or organization.

It was not until the year 1800 that she was christened with her present name; and when she did receive it, she obliged to share it in common with Michigan until 1805, and with Illinois until 1809. Besides, when at last she had a name all to herself, it was a second-hand one, having previously been borne by a 5000 square mile tract of land (approx. 10 counties) inside West Virginia (below) from about 1768 to 1798, a period of thirty years. How the name was obtained and finally lost by its original bearer, West Virginia is substantially as follows:

At the close of the French and Indian War, in 1763, the French having been forced from the Ohio Valley, a Philadelphia trading company was organized to monopolize the Indian trade of that region. This company consisted of twenty-five members, amongst whom George Morgan seems to have been the most active and prominent. As there was no other business at that time equally remunerative, these gentlemen invested a large amount of money in European goods for this trade, and, in the care of agents, a large quantity of them was sent down the Ohio Valley to be exchanged for furs and such other products of the chase as the Indians were accustomed to bring to the trading posts.

In order to understand fully the outcome of this venture, and its relation to the subject in hand, it is necessary to know a little of Indian history. At the time when the English began occupying the Atlantic seaboard of what is now the United States, there dwelt in the present State of New York, to the south of Lakes Ontario and Erie, the powerful and progressive tribes known as the Iroquois. By forming a confederacy, these five or six tribes had abolished that destructive competition among themselves which has always been a bar to the progress of civilization, and, as a consequence of their union, were able to live a settled life. At the time when permanent European occupation of the United States began, they had a strong and well disciplined army; they built houses, cultivated the fields, planted orchards, engaged in trade, and were developing some of the arts of civilized life and some of the pride and ambition which accompany the awakening of a national spirit. Like the early Romans, they were reaching out a conquering hand in every direction. They had subjugated the tribes of Canada to the north of Lakes Ontario and Erie, and also those of the eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and to the southward as far as Tennessee and North Carolina. They treated the conquered people as tributaries, and claimed their lands as their own by the same title as did their more highly civilized white brethren of the Old World, the right of conquest.

With these facts of Indian history in mind, let us now turn our attention again to the agents of the Philadelphia trading company, mentioned above.

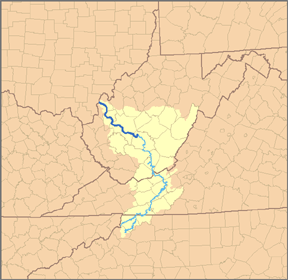

In the fall of the year 1763, some Indians of the Shawnee and other tribes, who were tributary to the Iroquois Confederacy, pounced upon the traders on the Ohio River, at a point below the present site of Wheeling, and, overpowering them, seized the goods and appropriated them to their own use. The Philadelphia company, on learning that their agents had been plundered, made complaint to the chiefs of the Six Nations, and demanded pay for their loss. These dusky Romans of the New World, like the Romans of old, feeling themselves responsible for the conduct of their subjects, admitted the justice of the claim; but as the plundered property was valued at nearly half a million dollars, the treasury of the confederacy did not contain sufficient cash to liquidate the debt. But if they had no money, they did claim a large amount of land, and five years later, in 1768, when making a boundary treaty with the English, the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy expressly reserved for the Philadelphia Company a tract nearly 5,000 square miles lying south of the Ohio River between Ohio and West Virginia and east of the Great Kanawha River. It included all of six, and a large part of five other counties within the present State of West Virginia.

Above, the Great Kanawha River in what is now West Virginia is in Blue. The 10 counties name Indiana were east of the Kanawha River and south of the Ohio River. The counties shown in Tan are not the exact group of West Virginia counties deeded to the Indiana Land Company and named the first Indiana land area but give you a pretty good idea of the location. The area was equal in extent to the State of Connecticut, more than twice that of Delaware, and about four times that of Rhode Island. The Philadelphia Company accepted the land in payment of their claim, and received a deed, prepared in due form, and signed by the six chiefs of the confederacy, and witnessed by the Governor and Chief Justice of New Jersey, and by several other gentlemen, representing Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, New York and the English Crown.

This princely domain now needs and must have a name. The proprietors were sufficiently scholarly to know how the names of States and countries were frequently made up. They had a number of examples in the Old World; as Wallachia, the land of the Wallachs; Bulgaria, the land of the Bulgars, or Volgars; Suabia, the land of the Suevi; Andalusia, or Vandalusia, the land of the Vandals, etc. But nearer home they had Virginia, the land of the Virgin (Queen Elizabeth); Pennsylvania, penn’s woodland; Georgia, the land of King George; Carolina, the land of Carolus, or Charles (II); Louisiana, the land of Louis (XIV of France), and so on through a long list. What more natural than that the proprietors should add the termination a, signifying land, to Indian, the name of the people from whom the land was obtained, and thus make up really euphonious name Indiana? This was done and the named applied the 10 county area inside West Virginia.

But now another bit of history must be traced in order to learn how the name came to be dropped from its original possessor (the Philadelphia Company) and applied to the present area we know today as the State of Indiana.

In 1776 this Indian land in West Virginia was transferred to a new company, known as the “Indiana Land Company,” and was then offered for sale; but as the land lay within the existing limits of West Virginia, she claimed it as her own by right of her charter. All through the Revolutionary War, and for many years after, the controversy went on between West Virginia and the Indiana Land Company. Settlers moved in, and the company demanded pay for the lands occupied by them; but West Virginia claimed jurisdiction over the settlers, and forbade the sale of land by the Indiana Land Company proprietors.

In 1779 the company petitioned Congress to interfere in its behalf, and such interference was attempted by a Congressional Committee in 1782. But Virginia continued obstinate, and as Congress was at that time operating under Articles of Confederation, it had no power to compel a State to do anything.

In 1790 the Indiana Land Company memorialized the legislature of Virginia, as it had done before, insisting that if the State was determined to hold the land, it should not do so without compensating the company. The proposition was hotly debated in the Virginia Assembly. The proprietors showed that, beside the original cost of the land covered by the cost of the plundered goods, they had spent over $18,000 trying to perfect their title. When the matter was brought to a vote there was a tie, but the casting vote of the Speaker decided the matter against the company. In 1791 another memorial was presented to the Virginia Legislature, but so far as appears no action was taken on it.

Before this time the Constitution of the United States had been adopted, and the Supreme Court established. The Indiana Company, despairing of justice at the hands of the Virginia legislature, entered suit in 1792 in the Supreme Court of the United States against the Commonwealth of Virginia for the recovery of their property. The Attorney-General of Virginia was subpoenaed by the United States Marshal to appear before the Court on the 4th of August, 1793, to answer to the complaint of the Indiana Company.

The sentiment of State rights, which so strongly prevailed in the earlier years of our national history, was perhaps more vigorously active in Virginia than anywhere else at the time, and the idea that a proud and sovereign State like the “Old Dominion” should be dragged before any tribunal outside of itself was exceedingly distasteful to her officers. Consequently, when the summons came for her to appear before the United States Supreme Court, they ignored it, declining to appear as defendant in the case of the Indiana Company. Her Legislature adopted a resolution in December, 1793, to the effect that she “is not bound and ought not to appear before the Supreme Federal Court.” She continued to refuse, and concentrated her efforts for securing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and it was successful, as is shown in the Eleventh Amendment, which reads:

“The judicial power of the "United States" shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity commenced or prosecuted against one of the States by citizens of another State, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign State.”

This amendment received the sanction of both houses of Congress early in 1794, and was sent out to the States for ratification. In the meantime, at the session of the Supreme Court in August, 1796, the case of the Indiana Company was called again, but Virginia did not respond, and before it was again called three-fourths of the States had ratified the proposed amendment (in 1798), and the long-contested case disappeared from the docket, and, as a consequence, the Indiana Land Company lost its claim and itself disappeared from view.

The land in question, having been absorbed by Virginia, had no further use for the "Indiana" name, and during the next two years the word Indiana expressed only a reminiscence of the past. Two years later in 1800, however, when Congress divided the Northwest Territory, and created the State of Ohio out of the eastern division, it took up the discarded name, Indiana, and applied it to the western division. It has ever since been retained by that portion which we “Hoosiers” affectionately regard as home. And as Paul Harvey used to say, "And now, you know the rest of the story.

PART OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORY BECOMES INDIANA

Prior to being named Indiana, the present-day area, now known as Indiana, became part of the Northwest Territory in 1787. In 1800, Ohio was separated from the Northwest Territory by Congress, designating the remainder of the land as the Indiana Territory.[12] President Thomas Jefferson chose William Henry Harrison as the Governor of the "territory" and Vincennes was established as the capital.[13] After Michigan was separated and the Illinois Territory was formed, the size of the Indiana Territory was reduced to its current state.[12] In 1810, Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa encouraged other tribes to resist European settlement into the territory. Supporters of Tecumseh formed Prophetstown while Harrison countered by building Fort Harrison nearby. The fort was often targeted by Prophetstown for attacks. Using the attacks as a reason to invade Prophetstown, Harrison went on the offensive and defeated the Native Americans in the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811. After the attack, Tecumseh, who was away during the battle, went to different tribes to encourage them to retaliate. For nearly two years, his followers killed and kidnapped settlers and burned their homes. Tecumseh was killed in 1813 during the Battle of Thames. After his death, while some Native Americans returned to their settlements, others fled the area or were forced to go further west.[14]

CAPITOL MOVED FROM VINCENNES TO CORYDON THREE YEARS PRIOR TO STATEHOOD AND TO INDIANAPOLIS NINE YEARS AFTER STATEHOOD, (ONE YEAR AFTER ROCKVILLE WAS FOUNDED)

In December 1813, Corydon was established as the capital of the Indiana Territory.[12] Two years later, a petition for statehood was approved by the Indiana legislature and sent to Congress. Afterwards, an Enabling Act was passed to provide an election of delegates to write a constitution for Indiana. On June 10, 1816, delegates assembled at Corydon to write the constitution, which was completed in nineteen days. President James Madison approved Indiana's admission into the union as the nineteenth state on December 11, 1816.[10] Nine years later, in 1825, the state capital was moved from Corydon to Indianapolis and 26 years later, a new constitution was adopted.[12] Following statehood, the new government set out on an ambitious plan to transform Indiana from a wilderness frontier into a developed, well-populated, and thriving state to accommodate for significant demographic and economic changes. The state's founders initiated a program that led to the construction of roads, canals, railroads and state-funded public schools. The plans nearly bankrupted the state and were a financial disaster, but increased land and produce value more than fourfold.[15]

THE CIVIL WAR

During the American Civil War, Indiana became politically influential and played an important role in the affairs of the nation. As the first western state to mobilize for the war, Indiana's soldiers were present in all of the major engagements during the war. Indiana residents were present in both the first and last battles and the state provided 126 infantry regiments, 26 batteries of artillery and 13 regiments of cavalry to the cause of the Union.[16] In 1861, Indiana was assigned a quota of 7,500 men to join the Union Army.[17] So many volunteered in the first call that thousands had to be turned away. Before the war ended, Indiana contributed 208,367 men to fight and serve in the war. Casualties were over 35% among these men: 24,416 lost their lives in the conflict and over 50,000 more were wounded.[18] The only Civil War battle fought in Indiana was the Battle of Corydon, which occurred during Morgan's Raid. The battle left 15 dead, 40 wounded, and 355 captured.[19]

Following the American Civil War, Indiana industry began to grow at an accelerated rate across the northern part of the state leading to the formation of labor unions and suffrage movements.[20] The Indiana Gas Boom led to rapid industrialization during the late 19th century.[21] In the early 20th century, Indiana developed into a strong manufacturing state.[22] The state also saw many developments with the construction of Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the takeoff of the auto industry.[23] During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, was affected by the Great Depression. The economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana, such as the decline of urbanization. The situation was aggravated by the Dust Bowl, which caused an influx of migrants from the rural Midwestern United States. Governor Paul V. McNutt's administration struggled to build a state-funded welfare system to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his administration, spending and taxes were both cut drastically in response to the depression and the state government was completely reorganized. McNutt also ended Prohibition in the state and enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law to put an end to worker strikes.[24] World War II helped lift the economy in Indiana, as the war required steel, food and other goods that were produced in Indiana.[25] Roughly 10 percent of Indiana's population joined the armed forces while hundreds of industries earned war production contracts and began making war material.[26] The effects of the war helped end the Great Depression.[25]

POST WORLD WAR II

With the conclusion of World War II, Indiana rebounded to levels of production prior to the Great Depression. Industry became the primary employer, a trend that continued into the 1960s. Urbanization during the 1950s and 1960s led to substantial growth in the state's urban centers. The auto, steel and pharmaceutical industries topped Indiana's major businesses. Indiana's population continued to grow during the years after the war, exceeding five million by the 1970 census.[27] In the 1960s, the administration of Matthew E. Welsh adopted its first sales tax of two percent.[28] Welsh also worked with the General Assembly to pass the Indiana Civil Rights Bill, granting equal protection to minorities in seeking employment.[29] Beginning in 1970, a series of amendments to the state constitution were proposed. With adoption, the Indiana Court of Appeals was created and the procedure of appointing justices on the courts was adjusted.[30] The 1973 oil crisis created a recession that hurt the automotive industry in Indiana. Companies like Delco Electronics and Delphi began a long series of downsizing that contributed to high unemployment rates in manufacturing in Anderson, Muncie, and Kokomo. The deindustrialization trend continued until the 1980s when the national and state economy began to diversify and recover.[31]

The State of Indiana (![]() i /?ndi?æn?/) is a U.S. state, the 19th admitted to the Union. It is located in the Great Lakes Region, and with approximately 6.3 million residents, is ranked 16th in population and 17th in population density.[4] Indiana is ranked 38th in land area, and is the smallest state in the continental US west of the Appalachian Mountains. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis, the largest of any state capital east of the Mississippi River.

i /?ndi?æn?/) is a U.S. state, the 19th admitted to the Union. It is located in the Great Lakes Region, and with approximately 6.3 million residents, is ranked 16th in population and 17th in population density.[4] Indiana is ranked 38th in land area, and is the smallest state in the continental US west of the Appalachian Mountains. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis, the largest of any state capital east of the Mississippi River.

Indiana has several metropolitan areas with populations greater than 100,000 as well as a number of smaller industrial cities and small towns. It is home to several major sports teams and athletic events including the NFL's Indianapolis Colts, the NBA's Indiana Pacers, the Indianapolis 500 motorsports race (which is the largest single-day sporting event in the world).

Residents of Indiana are known as Hoosiers, but the origin of the term is unknown. Many explanations are given, including the humorous ones of James Whitcomb Riley stating that Indiana pioneers would yell out "Who's There" in the wilderness or "Who's Ear?" after a brawl. The state's name means "Land of the Indians", or simply "Indian Land". This name dates back to at least the 1768 and was first used by Congress when the Indiana Territory was incorporated in 1800, before which it had been part of the Northwest Territory.[5][6]

Prior to this, Indiana had been inhabited by varying cultures of indigenous peoples and historic Native Americans for thousands of years. Angel Mounds State Historic Site, one of the best preserved ancient earthwork mounds sites in the United States, can be found in Southwestern Indiana near Evansville.[7]

THE LAND ORDINANCE OF 1785

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress on May 20, 1785. Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress did not have the power to raise revenue by direct taxation of the inhabitants of the United States. Therefore, the immediate goal of the ordinance was to raise money through the sale of land in the largely unmapped territory west of the original colonies acquired from Britain at the end of the Revolutionary War.

In addition, the act provided for the political organization of these territories. The earlier Ordinance of 1784 called for the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River to be divided into ten separate states. However, it did not define the mechanism by which the land would become states, or how the territories would be governed or settled before they became states. The Ordinance of 1785, along with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, were intended to address these political needs.

The 1785 ordinance laid the foundations of land policy in the United States of America until passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. The Land Ordinance established the basis for the Public Land Survey System. (SEE BELOW) The initial surveying was performed by Thomas Hutchins. After he died in 1789, responsibility for surveying was transferred to the Surveyor General. Land was to be systematically surveyed into square townships, six miles (9.656 km) on a side. Each of these townships were sub-divided into thirty-six sections of one square mile (2.59 km²) or 640 acres. These sections could then be further subdivided for sale to settlers and land speculators.

The ordinance was also significant for establishing a mechanism for funding public education. Section 16 in each township was reserved for the maintenance of public schools. Many schools today are still located in section sixteen of their respective townships, although a great many of the school sections were sold to raise money for public education.

In theory, the federal government also reserved sections 8, 11, 26 and 29 to compensate veterans of the Revolutionary War, but examination of property abstracts in Ohio indicates that this was not uniformly practiced. The ordinance also said “That three townships adjacent to Lake Erie be reserved, to be hereafter disposed of by Congress, for the use of the officers, men, and others, refugees from Canada, and the refugees from Nova Scotia, who are or may be entitled to grants of land under resolutions of Congress now existing.“ This was not possible, as the area next to Lake Erie was property of Connecticut, so the Canadians had to wait until the establishment of the Refugee Tract in 1798.[1]

The Point of Beginning for the 1785 survey was where Ohio (as the easternmost part of the Northwest Territory), Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia) met, on the north shore of the Ohio River near East Liverpool, Ohio. There is a historical marker just north of the site, at the state line where Ohio State Route 39 becomes Pennsylvania Route 68.

The Continental Congress appointed a committee consisting of

- Thomas Jefferson- Virginia Chairman

- Hugh Williamson- North Carolina

- David Howell- Rhode Island

- Elbridge Gerry- Massachusetts

- Jacob Read- South Carolina.

On May 7, 1784, the committee reported “An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of locating and disposing of lands in the western territories, and for other purposes therein mentioned.” The ordinance required the land be divided into “hundreds” of ten miles square, and subdivided into lots of one mile squared each, numbered starting in the northwest corner, proceeding from west to east, and east to west consecutively. After debate and amendment, the ordinance was reported to Congress April 26, 1785. It required surveyors “to divide the said territory into townships seven miles square, by lines running due north and south, and others crossing these at right angles. --- The plats of the townships, respectively, shall be marked into sections of one mile square, or 640 acres” This is the first recorded use of the terms “township” and “section.”[2]

On May 3, 1785, William Grayson of Virginia made a motion seconded by James Monroe to change “seven miles square” to “six miles square.” The ordinance was passed on May 20, 1785. The sections were to be numbered starting at 1 in the southeast and running south to north in each tier to 36 in the northwest. The surveys were to be performed under the direction of the Geographer of the United States, (Thomas Hutchins).[2] The Seven Ranges, the privately surveyed Symmes Purchase, and , with some modification, the privately surveyed Ohio Company of Associates, all of the Ohio Lands were the surveys completed with this section numbering[3].

The act of May 18, 1796 provided for the appointment of a surveyor-general to replace the office of Geographer of the United States, and that “sections shall be numbered, respectively, beginning with number one in the northeast section, and proceeding west and east alternately, through the township, with progressive numbers till the thirty-sixth be completed.” All subsequent surveys were completed with this section numbering system except the United States Military District of the Ohio Lands which had five mile square townships as provided by the Act of June 1, 1796 and amended by the Act of March 1, 1800.[2]

Thomas Hutchins is given credit for conceiving the rectangular system of lots of one square mile in 1764 while a captain in the sixtieth Royal-American regimen, and engineer to the expedition under Col. Henry Bouquet to the forks of the Muskingum, in what is now Coshocton County, Ohio. It formed part of his plan for military colonies north of the Ohio, as a protection against Indians. The law of 1785 embraced most of the new system.[4]

THE NORTHWEST ORDINANCE

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio, and also known as the Freedom Ordinance) was an act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States. The primary effect of the ordinance was the creation of the Northwest Territory as the first organized territory of the United States out of the region south of the Great Lakes, north and west of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi River. On August 7, 1789, the U.S. Congress affirmed the Ordinance with slight modifications under the Constitution.

Arguably the single most important piece of legislation passed by members of the earlier Continental Congresses other than the Declaration of Independence, it established the precedent by which the United States would expand westward across North America by the admission of new states, rather than by the expansion of existing states.

Further, the banning of slavery in the territory had the effect of establishing the Ohio River as the boundary between free and slave territory in the region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. This division helped set the stage for the balancing act between free and slave states that was the basis of a critical political question in American politics in the 19th century until the Civil War.

Acquired by Great Britain from France following the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the Ohio Country had been closed to white settlement by the Proclamation of 1763. The United States claimed the region after the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War, but was subject to overlapping and conflicting claims of the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Virginia, as well as a lingering British presence that was not settled until the War of 1812.

.png)

The region had long been desired for expansion by colonists, however, and urgency of the settlement of the claims of the states was prompted in large measure by the de facto opening of the area to settlement following the loss of British control.

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson proposed that the states should relinquish their particular claims to all the territory west of the Appalachians, and the area should be divided into new states of the Union. Thomas Jefferson's proposal of creating a national domain through state cessions of western lands came from earlier proposals dating back to 1776 debates about the Articles of Confederation.[1] Jefferson proposed creating seventeen roughly rectangular states from the territory, and even suggested names for the new states, including Chersonesus, Sylvania, Assenisipia, Metropotamia, Polypotamia, Pelisipia, Saratoga, Washington, Michigania and Illinoia. The proposal was adopted in a modified form, and without Jefferson's invented names, as the Northwest Ordinance of 1784. This ordinance established the example that would become the basis for the Northwest Ordinance three years later. Michigan, Illinois, and Washington would eventually be used as state names.

The 1784 ordinance was criticized by George Washington in 1785 and James Monroe in 1786. Monroe convinced Congress to reconsider the proposed state boundaries and a committee was formed which recommended repealing that part of the ordinance. Other politicians questioned the 1784 ordinance's plan for organizing governments in new states, and worried that the new states' relatively small size would undermine the original states' power in Congress. Other events such as the reluctance of states south of the Ohio River to cede their western claims resulted in a narrowed geographic focus.[1]

The passage of the ordinance followed the relinquishing of all such claims by the states over the territory, which was to be administered directly by Congress, with the intent of eventual admission of newly created states from the territory. The legislation was revolutionary in that it established the precedent for lands to be administered by the central government, albeit temporarily, rather than underneath the jurisdiction of particular states.

[edit] Admission of new states

The most significant intended purpose of this legislation was its mandate for the creation of new states from the region, once a population of 60,000 had been achieved within a particular territory. The actual legal mechanism of the admission of new states was established in the Enabling Act of 1802. The first state created from the territory was Ohio, in 1803.

[edit] Establishment of territorial government

As an organic act, the ordinance created a civil government in the territory under the direct jurisdiction of the Congress. The ordinance was thus the prototype for the subsequent organic acts that created organized territories during the westward expansion of the United States. It specifically provided for the appointment by Congress of a Territorial Governor with a three-year term, a Territorial Secretary with a four-year term, and three Judges, with no set limit to their term. As soon as there was a population of 5,000 "free male inhabitants of full age", they could form a general assembly for a legislature. In 1789, the U.S. Congress made minor changes, such that the President, with the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate, had the power to appoint and remove the Governor and officers of the territory instead of Congress. The Territorial Secretary was authorized to act for the Governor, if he died, was absent, was removed, or resigned from office.

[edit] Establishment of civil rights

The civil rights provisions of the ordinance foreshadowed the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Many of the concepts and guarantees of the Ordinance of 1787 were incorporated in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In the Northwest Territory, various legal and property rights were enshrined, religious tolerance was proclaimed, and it was enunciated that since "Religion, morality, and knowledge" are "necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." The right of habeas corpus was written into the charter, as was freedom of religious worship and bans on excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment. Trial by jury and a ban on ex post facto laws were also rights granted.

[edit] Prohibition of slavery

The ordinance prohibited slavery in the region, at a time when northeastern states such as New York and New Jersey still permitted it. The text of the ordinance read, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." In reality, slaves were (illegally) kept in parts of the territory, and the practice of indentured servitude was legal.

In the decades preceding the American Civil War, the abolition of slavery in the northeast by the 1830s created a contiguous region of free states to balance the Congressional power of the slave states in the south. After the Louisiana Purchase, the Missouri Compromise effectively extended the Ohio River boundary between free and slave territory westward from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains. The balance between free and slave territory established in the ordinance eventually collapsed following the Mexican-American War.

Many "fire-eater" Southerners of the 1850s denied that Congress even had the authority to bar the spread of slavery to the Northwest Territory. President George Washington did not advocate the abolition of slavery while in office, but signed legislation enforcing the prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory, writing to his good friend the Marquis de la Fayette that he considered it a wise measure. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison both wrote that they believed Congress had such authority.

[edit] Definition of the Midwest as a region

The Northwest Ordinance, along with the Land Ordinance of 1785, laid the legal and cultural groundwork for midwestern (and subsequently, western) development. Significantly, the free state legal philosophies of both Abraham Lincoln and Salmon P. Chase (Chief Justice, Senator, and early Ohio law author) were derived from the Northwest Ordinance.

[edit] Effects on Native Americans

The Northwest Ordinance also made mention of Native Americans: "The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed," which was more a nominal provision than a real one. Many American Indians in Ohio refused to defer to treaties signed after the Revolutionary War that ceded lands north of the Ohio River (inhabited by American Indians) to the United States. In a conflict sometimes known as the Northwest Indian War, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Little Turtle of the Miamis formed a confederation to stop white expropriation of the territory. After the Indian confederation had killed more than 800 soldiers in two battles — the worst defeats ever suffered by the U.S. at the hands of the Indians — President Washington assigned General Anthony Wayne command of a new army, which eventually defeated the confederation and thus allowed whites to continue settling the territory.

Public Land Survey System

The Public Land Survey System (PLSS) is a method used in the United States to survey and identify land parcels, particularly for titles and deeds of rural, wild or undeveloped land. Its basic units of area are the township and section. It is sometimes referred to as the rectangular survey system, although non rectangular methods such as meandering can also be used. The survey was "the first mathematically designed system and nationally conducted cadastral survey in any modern country" and is "an object of study by public officials of foreign countries as a basis for land reform." [1] The detailed survey methods to be applied for the PLSS are described in a series of Instructions and Manuals issued by the General Land Office, the latest edition being the "The Manual of Instructions for the Survey of the Public Lands of the United States, 1973" available from the U.S. Government Printing Office. The BLM announced in 2000 an updated Manual is currently under preparation.

The system was created by the Land Ordinance of 1785. It has been expanded and slightly modified by Letters of Instruction and Manuals of Instruction, issued by the General Land Office and the Bureau of Land Management and continues in use in most of the states west of Pennsylvania, south to Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi, west to the Pacific Ocean, and north into the Arctic in Alaska.

[edit] Origins of the system

The original colonies (including their derivatives Maine, Vermont, Tennessee, Kentucky and West Virginia) continued the British system of metes and bounds. This system describes property lines based on local markers and bounds drawn by humans, often based on topography. A typical, yet simple, description under this system might read "From the point on the north bank of Muddy Creek one mile (1.6 km) above the junction of Muddy and Indian Creeks, north for 400 yards, then northwest to the large standing rock, west to the large oak tree, south to Muddy Creek, then down the center of the creek to the starting point."

Particularly in New England, this system was supplemented by drawing up town plats. The metes-and-bounds system was used to describe a town of a generally rectangular shape, 4 to 6 miles (~6 to 10 km) on a side. Within this boundary, a map or plat was maintained that showed all the individual lots or properties.

There are some difficulties with this system:

- Irregular shapes for properties make for much more complex descriptions.

- Over time, these descriptions become problematic as trees die or streams move by erosion.

- It wasn't useful for the large, newly surveyed tracts of land being opened in the west, which were being sold sight unseen to investors.

In addition this system didn't work until there were already people on the ground to maintain records. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris recognizing the United States, Britain also recognized American rights to the land south of the Great Lakes and west to the Mississippi River.

The Continental Congress passed the Land Ordinance of 1785 and then the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 to control the survey, sale, and settling of the new lands. The original 13 colonies donated their western lands to the new Union, for the purpose of giving land for new states. These include the lands that formed the Northwest Territory, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi. The state that gave up the most was Virginia, whose original claim included most of the Northwest Territory and Kentucky, too. Some of the western land was claimed by more than one state, especially in the Northwest, where parts were claimed by Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, all three of which had claimed lands all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

[edit] Applying the system

The first surveys under the new rectangular system were in eastern Ohio in an area called the Seven Ranges.

The Beginning Point of the U.S. Public Land Survey is a United States National Historic Landmark, near Glasgow, PA at the Ohio-Pennsylvania border.

Ohio was surveyed in several major subdivisions, collectively described as the Ohio Lands, each with its own meridian and baseline. The early surveying, particularly in Ohio, was performed with more speed than care, with the result that many of oldest townships and sections vary considerably from their prescribed shape and area. Proceeding westward, accuracy became more of a consideration than rapid sale, and the system was simplified by establishing one major north-south line (principal meridian) and one east-west (base) line that control descriptions for an entire state or more. For example, a single Willamette Meridian serves both Oregon and Washington. County lines frequently follow the survey, so there are many rectangular counties in the Midwest and the West.

[edit] Non-PLSS regions

The system is in use in some capacity in most states, but not in Hawaii and Texas or any of the territory under the jurisdiction of the Thirteen Colonies at the time of independence, with the exception of the area that became the Northwest Territory and some of the Southern states. These exclusions are now Georgia, Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia.

The old Cherokee lands in Georgia use the term section as a land designation, but does not define the same area as the section used by the PLSS.

Major exceptions to the application of this system in the remaining states:

- California, before statehood in 1850, surveyed only the boundaries of Spanish land grants (ranchos); since statehood the PLSS system has been used throughout.

- Hawaii adopted a system based on the Kingdom of Hawaii native system in place at the time of annexation.

- Louisiana recognizes early French and Spanish descriptions called arpents, particularly in the southern part of the state, as well as PLSS descriptions.

- Maine uses a variant of the system in unsettled parts of the state.

- New Mexico uses the PLSS, but has several areas that retain original metes and bounds left over from Spanish and Mexican rule. These take the form of land grants similar to areas of Texas and California.

- Ohio's Virginia Military District was surveyed using the metes and bounds system. Areas in northern Ohio (primarily what originally was the Connecticut Western Reserve) were surveyed with an earlier standard, often referred to as Congressional Survey townships, which are just five miles (8 km) on each side instead of six. Hence, there are 25 sections per township there, rather than 36.

- Texas has a hybrid of its own early system, based on Spanish land grants, and a variation of the PLSS.